Geopolitical Update (GU): AUKUS, France, and Asia

The who, what, when, and why of this surprise announcement.

What has happened?

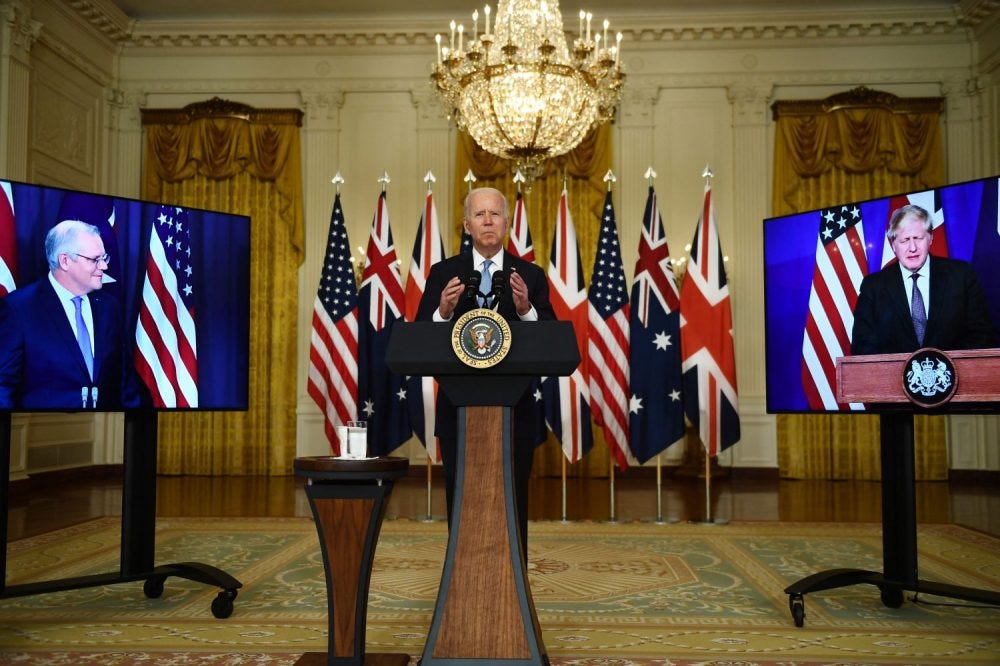

This week in a joint press conference Australian and British Prime Misters Morrison and Johnson, along with President of the United States Joe Biden, announced a new defense and technology pact. This pact officially includes eight new nuclear-powered submarines for the Australian Navy and technology transfers for their construction from the United States and the UK.

Unofficially, the deal likely includes expanded basing rights for US and UK ships in Australian ports, opens negotiations for leasing an older US sub to train Australian crews, self-defense clauses similar to NATO’s article five, and more in-depth intel sharing than those already conducted as part of the five eyes (five members: Australia, US, UK, Canada, and New Zeland) intel sharing program.

The controversy revolves around acquiring eight nuclear submarines from the US and UK as previously the Australian Navy had agreed to in 2016 to acquire twelve French diesel-powered “Scorpene” submarines to replace the aging “Collins” class. The 2016 agreement originally authorized $36 billion for the planning, shipyard construction in Australia, and acquisition of the submarines but has since ballooned to over $66 billion as French builders failed to deliver a single submarine. After missing the March deadline for providing the first submarine set by PM Morrison early in 2020, the Australians terminated the contract with the French government in favor of the deal with the US and UK.

So what comes next?

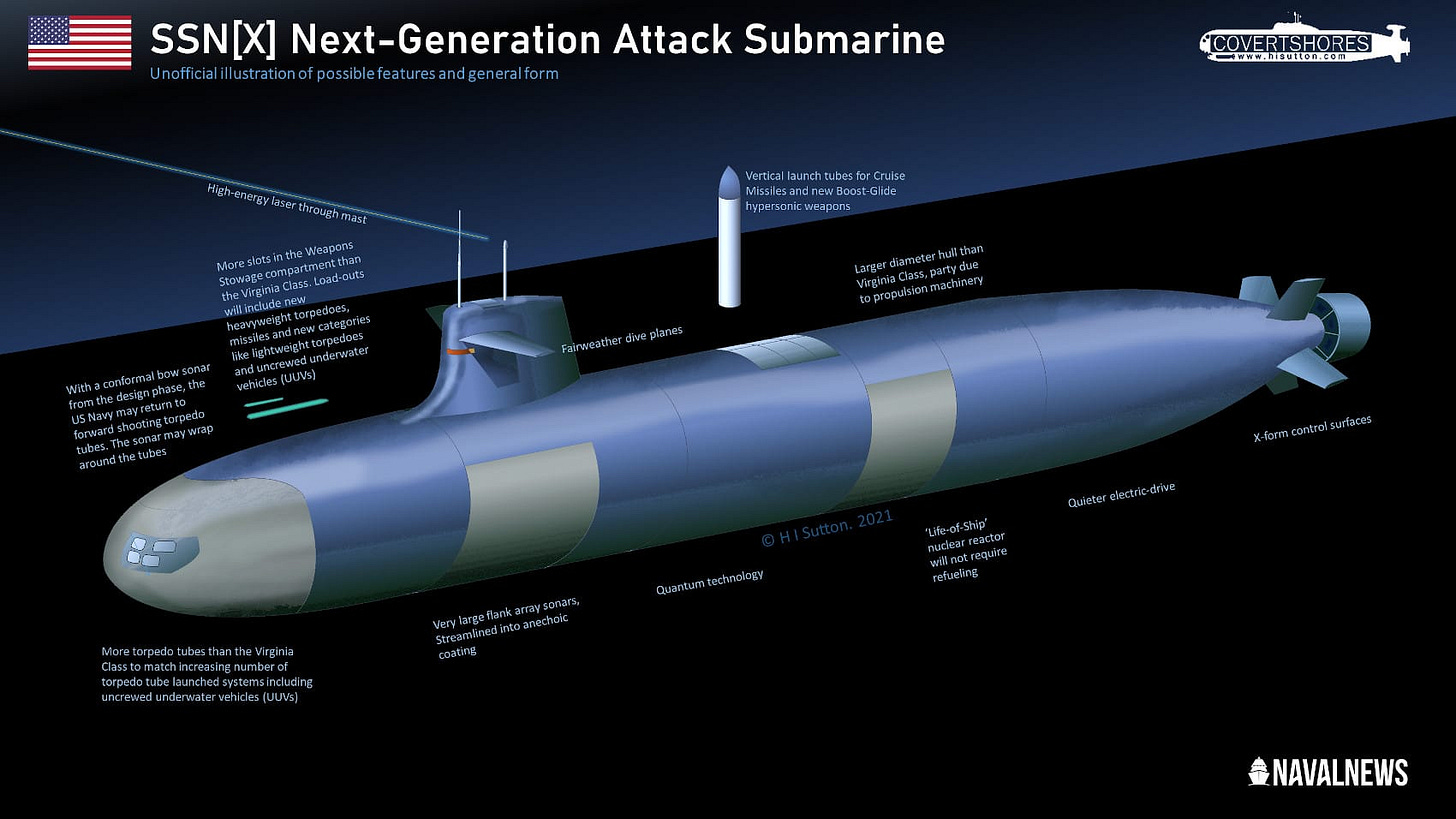

Well expanding members will likely be the first public action to occur as India and Japan have loudly lauded the new agreement knowing full well they will be the next two nations to petition for their ascendency to the pact. Unofficially, US and UK contractors are likely to merge their conceptual designs for the next generation of nuclear attack submarines, especially from the US as the Virginia class gets closer to concluding its production run. This deal, for US shipbuilders, is the perfect opportunity to let the Australian government carry the cost overruns and discover the production issues that the US Navy can avoid when they ramp up the shipyards to produce its iterations.

Additionally, the Australian Navy has no experience sailing a nuclear submarine, likely requiring a leasing agreement with the UK or US of a pre-existing boat that neither nation would miss having from its fleet. Possible contenders are the HMS Triumph and Talent, the two oldest UK attack boats in the Royal Navy, or the USS Jacksonville, which is in a state of inactive reserve.

What features can we expect in the next generation of Australian Submarines? First and foremost, automation. The Australian Navy already struggles to recruit volunteers for its submarine service even with an aggressive signup bonus on offer. In addition, the Collins Class requires 40-50 crew which is half of the regular crew complement for nuclear submarines. Thus if the Australian navy plans to maintain the goal of acquiring eight nuclear submarines, automation of many systems will be a must to keep crew size to a scant seventy-five to ninety sailors.

Second, the submarines will be cruise missile capable with the potential to be upgraded to store hypersonics. While hypersonics remains more a possibility more than certainty, the announcement that the Australian military will be acquiring seaborne Tomahawk missiles in considerable quantities leaving the door open to surface ship and sub-surface deployment. Such weapons allow Submarines to attack inland surface targets and large surface ships like carriers and destroyers from a safe distance. Weapons that will be very effective in a hypothetical conflict over Taiwan.

Third and finally, this opens the door to a platform for a hypothetical Australian seaborne nuclear deterrent. While all partners openly deny this as a possible outcome, such a promise contradicts the direction the region is already pursuing. South Korea, for example, last week successfully launched its first SSBM (sub-surface ballistic missile) from one of its diesel submarines with the French, sour from the loss of their Australian deal, already offering to exchange nuclear submarine technology. Japan as well, possessing a competent nuclear industry and rapidly expanding its Navy, is likely to produce its own nuclear submarine by the end of the decade.

Conclusion:

In this ever-expanding global disorder, AUKUS demonstrates a different kind of US foreign policy. One that is focused around and considerably more generous to its core allies and conspicuously absent from global accords, affairs, and policing. A world where NATO’s and the EU’s legitimacy, longevity, and mandate are under increasing pressure and question. A region where Asia’s power brokers are increasingly seeking new alliances, guarantors, and economic relationships to counteract a revisionist power embodied by the People’s Republic of China. I very much look forward to seeing what comes next.